What Does the 2025 Nobel Prize in Physics Actually

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences announced that the 2025 Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to John Clarke, Michel H. Devoret, and John M. Martinis for a series of experiments showing how quantum‑world effects can appear in systems large enough to be observed with classical engineering instruments.

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences announced that the 2025 Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to John Clarke, Michel H. Devoret, and John M. Martinis for a series of experiments showing how quantum‑world effects can appear in systems large enough to be observed with classical engineering instruments.

In superconducting electrical circuits, quantum tunnelling occurs between two states – as if a particle could pass straight through a wall.

The laureates demonstrated that such systems can absorb and emit discrete packets of energy exactly as predicted by quantum mechanics.

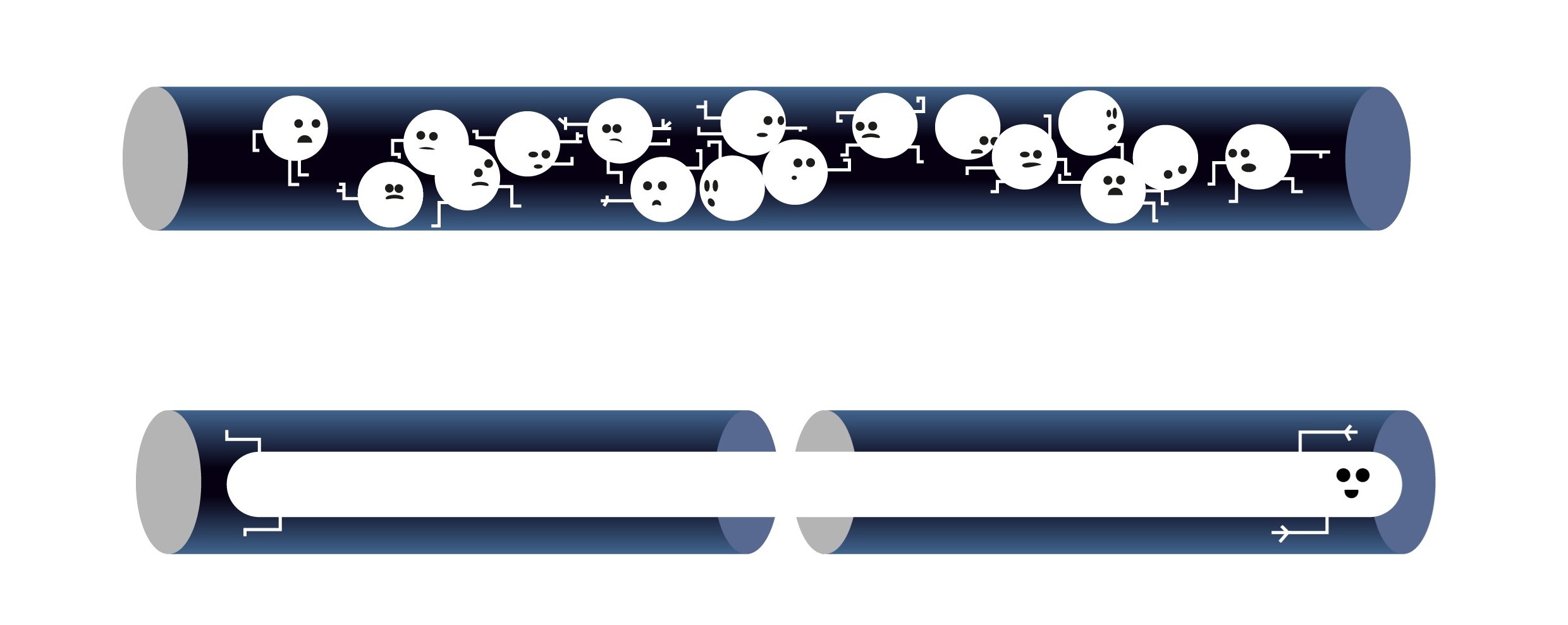

In quantum physics, quantum effects are usually considered microscopic – so small that they cannot be seen even with an optical microscope.

The everyday world around us, called the macroscopic world, is composed of vast numbers of particles, and quantum‑mechanical effects normally vanish from view.

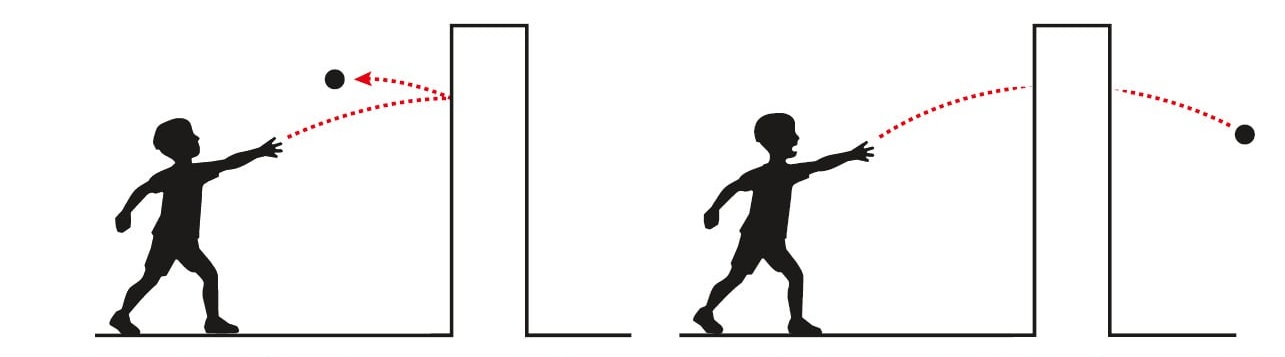

Everyone knows that a ball bouncing off a wall simply rebounds, yet quantum mechanics predicts that particles can sometimes pass through the wall and appear on the other side.

This microscopic phenomenon, known as tunnelling, is typically observed only in the micro‑realm.

In 1984–1985, John Clarke, Michel Devoret, and John Martinis at the University of California carried out a series of physics experiments on electrical circuits exhibiting superconductivity.

Superconductivity is the phenomenon in which a material loses its electrical resistance, so energy losses become extremely small.

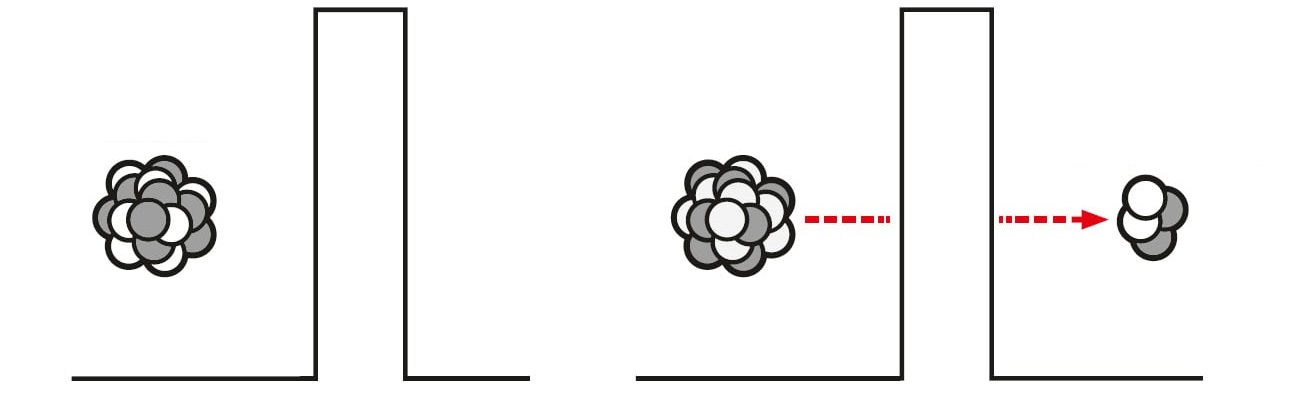

Knowing that quantum phenomena can be detected at low temperatures, the physicists began to explore whether a tunnelling process could occur that involved several particles simultaneously.

A quantum superposition of two electrons forming a single shared quantum state is called a Cooper pair.

Cooper pairs behave completely differently from individual electrons: they can be described as a single entity and, in quantum mechanics, as a wave – a wave function.

Extending this idea, an entire electrical circuit can be regarded as one quantum particle governed by the laws of quantum mechanics.

When two superconductors are connected by a thin barrier, a Josephson junction is formed – a quantum phenomenon named after physicist Brian Josephson.

In 1962, Josephson predicted from quantum‑mechanical principles that a current could flow through such a structure without any applied voltage, a discovery that earned him the 1973 Nobel Prize in Physics.

Later, in 2003, Anthony Leggett received the Nobel Prize for his theoretical description of macroscopic quantum tunnelling in Josephson junctions.

This topic attracted the attention of John Clarke’s research group in California, joined by Michel Devoret and John Martinis.

They developed an experimental methodology for preparing Cooper pairs, observing them, and determining their properties.

Their key achievement was demonstrating that Cooper pairs can act synchronously – as a single quantum entity.

Physical experiments not only deepen our understanding of quantum mechanics – including macroscopic effects in lasers, superconductors, and superfluid systems – but also make it possible to apply quantum theory in engineering, especially in quantum technologies.

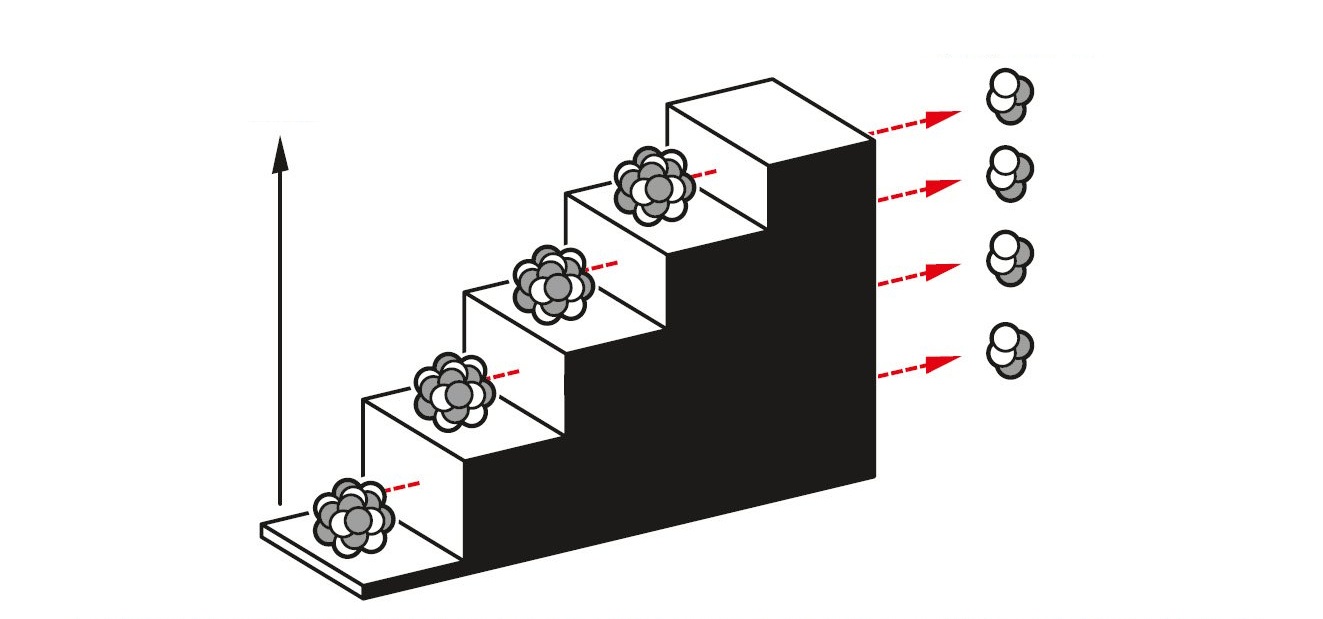

In his experiments, John Martinis demonstrated quantum bits, or qubits, which became a cornerstone in building quantum computers.

To create qubits, physicists require a quantum system that can be described as an anharmonic oscillator – precisely the case for the model of Cooper electron pairs.

A magnetic field forms a barrier through which tunnelling occurs.

By using microwaves, engineers can vary the amplitudes of the tunnelling oscillations, while several qubits coupled through magnetic fields and Josephson junctions establish quantum entanglement.

Such indeterminate quantum states are often compared to the famous Schrödinger’s cat – a system that is neither 0 nor 1 until measured.

When engineers perform a current measurement, the system collapses into one of two classical states, producing a definite result: 0 or 1.

This opens the way to quantum computers whose operation is based on quantum tunnelling realized in macroscopic devices.

Quantum computers already exist – for example, D‑Wave and IBM Condor, the first superconducting‑qubit processor to exceed 1 000 qubits.

It is likely that future quantum computers – not necessarily relying on tunnelling or superconductivity alone – will surpass today’s most powerful supercomputers and solve scientific problems that we can currently tackle only approximately.

Breakthroughs may therefore be expected in artificial intelligence, in the search for more effective medicines, and in a deeper understanding of the fundamental laws of nature.